Productivity in knowledge work feels broken. We never figured out how to measure it properly, and now AI is collapsing its perceived value.

This isn't a temporary disruption. It's a structural shift that will reshape how organizations think about talent, skills, and competitive advantage. The parallel to manufacturing's transformation over the past three decades is striking, and the implications are profound.

The Measurement Problem That Made Us Vulnerable

Manufacturing productivity has always had an absolute anchor: widgets per hour, raw materials with fixed costs. Value is grounded in something tangible. When you produce 100 units instead of 80, the improvement is unambiguous.

Knowledge work floats on a relative scale: price per alleged quality of dynamically changing work. The raw materials of knowledge work are skill, expertise, and attention. These are incredibly difficult to quantify. Research on measuring employee engagement has long struggled with this challenge, often relying on self-reported sentiment rather than observable behaviors.

When the only benchmark is "how little will someone else charge for similar output," the direction is inevitably down. AI accelerates this race to the bottom by producing adequate-looking work at near-zero marginal cost.

Worse, AI masks the absence of expertise remarkably well. A mediocre analysis and an expert one can look identical on the surface. The difference reveals itself in outcomes, often months later. This creates what researchers call a "quality verification problem" that traditional productivity metrics fail to capture.

The China Shock Parallel

AI is doing to knowledge work what China did to manufacturing.

When China entered global manufacturing following its WTO accession in 2001, it created massive cost arbitrage. The "China Shock," as economists now call it, displaced approximately 1 in 7 U.S. manufacturing workers in heavily exposed regions (Autor, Dorn, Hanson, Jones & Setzler, 2025). Quality was initially lower, then improved. Competing on price became impossible for many domestic producers.

Research from the National Bureau of Economic Research reveals a striking pattern: local labor markets more exposed to Chinese import penetration experienced larger reallocation from manufacturing to services. About 40% of manufacturing job losses came from establishments switching their primary activity entirely, moving from production to trade-related services like research, management, and wholesale (Acemoglu et al., 2024).

The middle hollowed out. What survived? High-end work (design, engineering, brand) and specialized niches. The commodity middle collapsed. But critically, the recovery came not from displaced workers finding new roles, but from entirely new entrants to the workforce, particularly young adults and immigrants who never worked in manufacturing at all (Autor et al., 2025).

Knowledge Work Is Following the Same Pattern

Knowledge work is following the same pattern, compressed into years instead of decades.

Recent experimental research demonstrates the scale of AI's impact on productivity. A study of over 700 Boston Consulting Group consultants found that those using GPT-4 completed 12.2% more tasks, finished 25.1% faster, and produced 40% higher quality results compared to a control group (Dell'Acqua et al., 2023). Another study of customer service agents found that AI assistance increased productivity by 14-15% on average (Brynjolfsson, Li & Raymond, 2023).

Commodity work like routine analysis, standard reports, and generic content is collapsing first. These are the knowledge work equivalents of labor-intensive manufacturing, the tasks most easily replicated by lower-cost alternatives.

What will survive? Work requiring judgment, taste, relationships, and expertise that AI can't replicate. The organizations that understand this shift are already investing differently in their people, focusing on skills development and continuous performance feedback rather than just task completion.

Why Skill Gaps Will Matter More, Not Less

We may not avoid this race to the bottom. But skill gaps will matter more, not less.

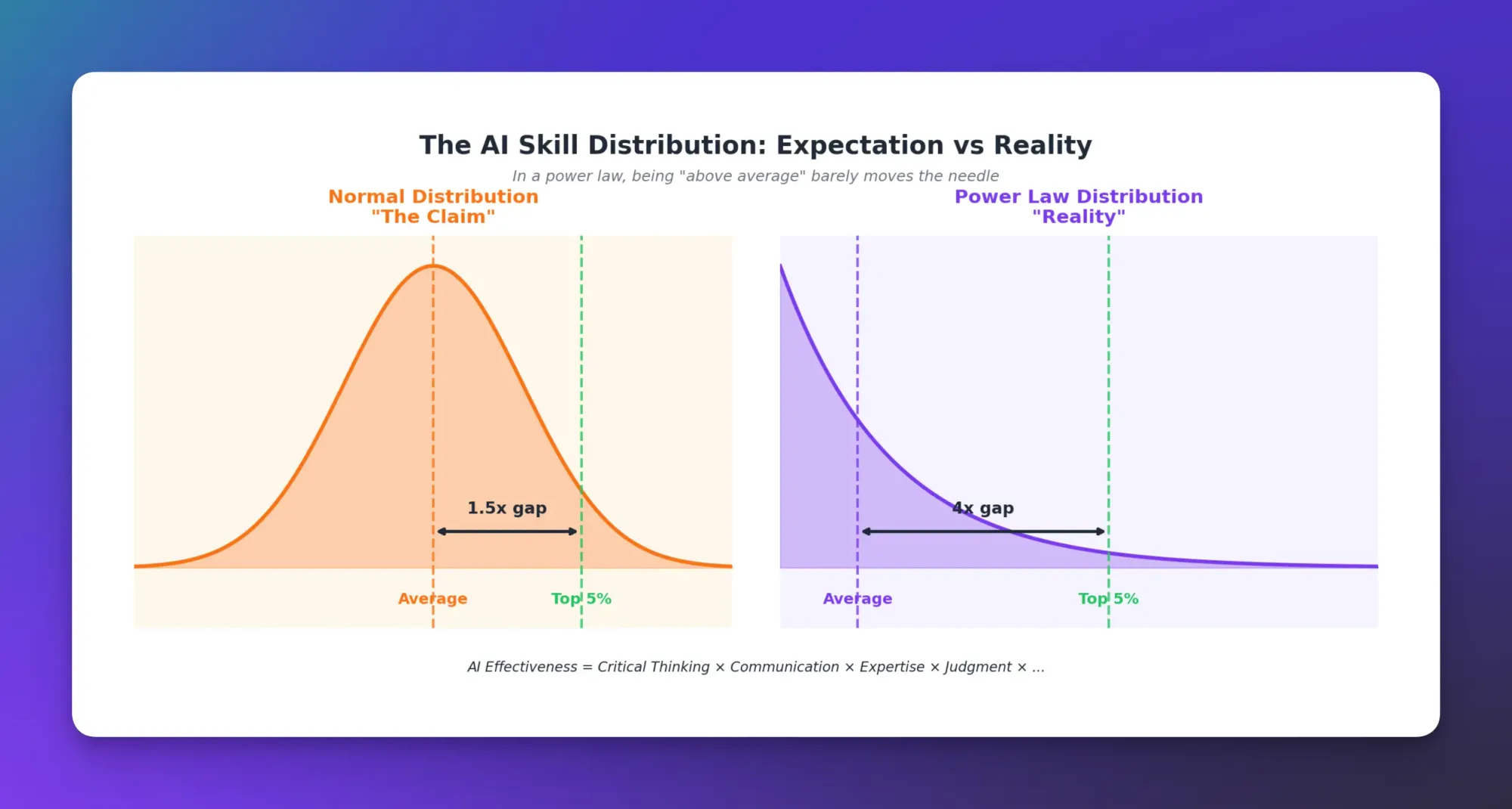

AI evangelists claim that AI skill follows a normal distribution. Everyone gets a little better. The average rises. The math doesn't check out.

AI skill follows a power law distribution, similar to income. Research in econophysics has demonstrated that income and wealth distributions consistently follow power laws rather than normal distributions, with the top segments capturing disproportionate shares of total value (Pareto, 1897; Gabaix, 2009). Studies of 633,263 individuals across researchers, entertainers, politicians, and athletes found that performance in 94% of these groups did not follow a normal distribution (O'Boyle & Aguinis, 2012).

The gap between the median and the top 5% is enormous and growing. This happens because the factors that make someone effective with AI are multiplicative, not additive:

Critical thinking × Communication × Domain expertise × Judgment × ...

If any of these is near zero, the product collapses. Multiplicative processes generate power law distributions precisely because small differences in underlying factors compound into large outcome differences (Gibrat, 1931; Gabaix, 2009). You can't prompt your way past weak critical thinking. You can't automate taste. AI amplifies what's already there.

The Research on AI and Skill Distribution

The evidence on how AI affects workers at different skill levels is nuanced and important.

Studies consistently find that lower-skilled workers see the largest relative productivity gains from AI tools. In the customer service study, novice and low-skilled workers improved by 34%, while high-skilled workers saw minimal impact (Brynjolfsson et al., 2023). The BCG consulting study found that consultants below the average performance threshold increased output by 43%, while those above increased by 17% (Dell'Acqua et al., 2023).

This might seem to suggest AI is an equalizer. But there's a critical caveat: these studies measure performance on tasks within AI's capability frontier. When researchers tested tasks outside that frontier, a different pattern emerged. Workers who relied heavily on AI for tasks it couldn't actually perform well saw their performance decline, sometimes significantly.

More importantly, the question isn't just about individual task performance. It's about who captures the value created. In power law distributions, small differences in capability translate to large differences in outcomes. The research on recognition patterns in organizations shows similar dynamics: a small percentage of contributors generate disproportionate value.

The Uncomfortable Implications

It's looking like being better than average with AI doesn't matter. Being in the top 5% does. And it's the superior critical thinking, domain expertise, and judgment that will make the difference.

This has profound implications for how organizations should approach talent development:

1. Invest in foundational skills, not shortcuts. The best at using AI never took a prompt engineering course. That's like taking dating classes when in fact what really matters is your personality. Organizations should prioritize behavioral feedback systems that develop critical thinking, communication, and domain expertise.

2. Measure what actually matters. Traditional engagement surveys capture sentiment, not capability. Behavioral measurement approaches that track observable actions provide better signals of who is developing the skills that will matter.

3. Recognize that management quality becomes more critical. Research shows that exceptional managers create environments where skill development accelerates. In a world where skill gaps determine value capture, the quality of your managers directly impacts your competitive position.

4. Design for the skills that compound. Just as successful manufacturers moved up the value chain to design and brand, knowledge work organizations need to identify and invest in the capabilities that AI amplifies rather than replaces.

How Happily.ai Approaches This Challenge

At Happily.ai, we've built our platform around the recognition that the future of work depends on developing the human capabilities that matter most. Our approach uses behavioral analytics rather than sentiment surveys because actions reveal capability more accurately than self-reports.

Our Dynamic Engagement Behavior Index (DEBI) tracks the behaviors that indicate genuine engagement: contributing high-quality feedback, recognizing peers for values-aligned work, and maintaining strong collaborative relationships. These behaviors correlate with the skills that AI amplifies.

Our continuous performance management system helps managers identify skill gaps early and provide the feedback that accelerates development. Research shows that consistent, high-quality feedback is the most effective intervention for skill development (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

The organizations that thrive in this new environment won't be those that adopt AI fastest. They'll be those that develop the human capabilities that make AI most valuable.

Looking Forward

The transformation of knowledge work will likely compress decades of manufacturing disruption into years. The organizations that understand this shift have an opportunity to build sustainable competitive advantage by investing in human capabilities while others focus solely on AI adoption.

The path forward isn't about resisting AI or embracing it uncritically. It's about understanding that AI changes what skills matter, then building the systems that develop those skills systematically.

The commodity middle of knowledge work will continue to collapse. The question for every organization is whether they're positioned in the high-value work that survives and thrives, or competing for the shrinking margins of easily-replicated output.

References

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G. H., & Price, B. (2024). The China shock revisited: Job reallocation and industry switching in U.S. labor markets. NBER Working Paper No. 33098.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G. H., Jones, M. R., & Setzler, B. (2025). Places versus people: The ins and outs of labor market adjustment to globalization. NBER Working Paper No. 33424.

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. R. (2023). Generative AI at work. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 140(2), 889-938.

Dell'Acqua, F., McFowland III, E., Mollick, E. R., Lifshitz-Assaf, H., Kellogg, K., Rajendran, S., Krayer, L., Candelon, F., & Lakhani, K. R. (2023). Navigating the jagged technological frontier: Field experimental evidence of the effects of AI on knowledge worker productivity and quality. Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 24-013.

Gabaix, X. (2009). Power laws in economics and finance. Annual Review of Economics, 1, 255-293.

Gibrat, R. (1931). Les inégalités économiques. Librairie du Recueil Sirey.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112.

O'Boyle, E., & Aguinis, H. (2012). The best and the rest: Revisiting the norm of normality of individual performance. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 79-119.

Pareto, V. (1897). Cours d'économie politique. Rouge.

Exploring the intersection of people analytics, organizational culture, and behavioral science to build thriving workplaces.